What We Talk About When We Talk About Money

An interview with artist Zane Fix

If you’d like to support the magazine and read this in print, please consider subscribing via Substack or ordering a copy from our website. This money goes directly towards paying contributors, hosting events, and creating print issues.

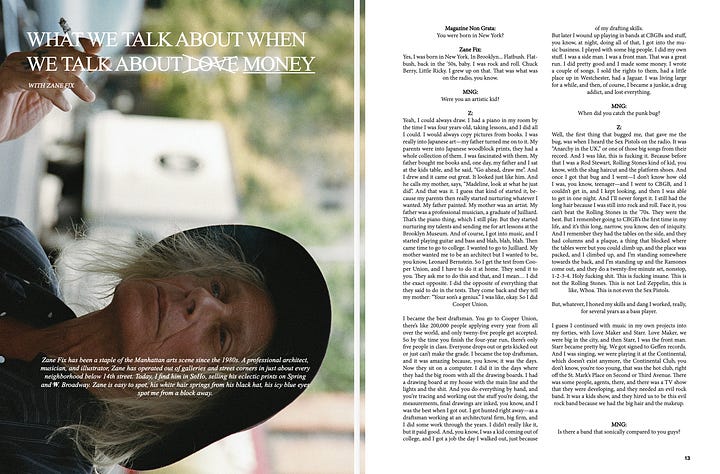

Zane Fix has been a staple of the Manhattan arts scene since the 1980s. A professional architect, musician, and illustrator, Zane has operated out of galleries and street corners in just about every neighborhood below 14th street. Today, I find him in SoHo, selling his eclectic prints on Spring and W. Broadway. Zane is easy to spot, his white hair springs from his black hat, his icy blue eyes spot me from a block away.

Magazine Non Grata

You were born in New York?

Zane Fix

Yes, I was born in New York. In Brooklyn... Flatbush. Flatbush, back in the ‘50s, baby. I was rock and roll. Chuck Berry, Little Ricky. I grew up on that. That was what was on the radio, you know.

MNG

Were you an artistic kid?

Z

Yeah, I could always draw. I had a piano in my room by the time I was four years-old, taking lessons, and I did all I could. I would always copy pictures from books. I was really into Japanese art—my father turned me on to it. My parents were into Japanese woodblock prints, they had a whole collection of them. I was fascinated with them.

My father bought me books and, one day, my father and I sat at the kids table, and he said, “Go ahead, draw me”. And I drew and it came out great. It looked just like him. And he calls my mother, says, “Madeline, look at what he just did”. And that was it. I guess that kind of started it, because my parents then really started nurturing whatever I wanted.

My father painted. My mother was an artist. My father was a professional musician, a graduate of Juilliard. That’s the piano thing, which I still play. But they started nurturing my talents and sending me for art lessons at the Brooklyn Museum. And of course, I got into music, and I started playing guitar and bass and blah, blah, blah.

Then came time to go to college. I wanted to go to Juilliard. My mother wanted me to be an architect but I wanted to be, you know, Leonard Bernstein. So I get the test from Cooper Union, and I have to do it at home. They send it to you. They ask me to do this and that, and I mean... I did the exact opposite. I did the opposite of everything that they said to do in the tests. They come back and they tell my mother: “Your son’s a genius.” I was like, okay. So I did Cooper Union.

I became the best draftsman. You go to Cooper Union, there’s like 200,000 people applying every year from all over the world, and only twenty-five people get accepted. So by the time you finish the four-year run, there’s only five people in class. Everyone drops out or gets kicked out or just can’t make the grade. I became the top draftsman, and it was amazing because, you know, it was the days. Now they sit on a computer. I did it in the days where they had the big room with all the drawing boards. I had a drawing board at my house with the main line and the lights and the shit. And you do everything by hand, and you’re tracing and working out the stuff you’re doing, the measurements, final drawings are inked, you know, and I was the best when I got out.

I got hunted right away as a draftsman working at an architectural firm, big firm, and I did some work through the years. I didn’t really like it, but it paid good. And, you know, I was a kid coming out of college, and I got a job the day I walked out, just because of my drafting skills.

But later I wound up playing in bands at CBGBs and stuff, you know, at night, doing all of that, I got into the music business. I played with some big people. I did my own stuff. I was a side man. I was a front man. That was a great run. I did pretty good and I made some money. I wrote a couple of songs. I sold the rights to them, had a little place up in Westchester, had a Jaguar. I was living large for a while, and then, of course, I became a junkie, a drug addict, and lost everything.

MNG

When did you catch the punk bug?

Z

Well, the first thing that bugged me, that gave me the bug, was when I heard the Sex Pistols on the radio. It was “Anarchy in the UK,” or one of those big songs from their record. And I was like, this is fucking it. Because before that I was a Rod Stewart, Rolling Stones kind of kid, you know, with the shag haircut and the platform shoes.

And once I got that bug and I went—I don’t know how old I was, you know, teenager—and I went to CBGB, and I couldn’t get in, and I kept looking, and then I was able to get in one night. And I’ll never forget it. I still had the long hair because I was still into rock and roll. Face it, you can’t beat the Rolling Stones in the ‘70s. They were the best. But I remember going to CBGB’s the first time in my life, and it’s this long, narrow, you know, den of iniquity. And I remember they had the tables on the side, and they had columns and a plaque, a thing that blocked where the tables were but you could climb up, and the place was packed, and I climbed up, and I’m standing somewhere towards the back, and I’m standing up and the Ramones come out, and they do a twenty-five minute set, nonstop, 1-2-3-4. Holy fucking shit. This is fucking insane. This is not the Rolling Stones. This is not Led Zeppelin, this is like, Whoa. This is not even the Sex Pistols.

But, whatever, I honed my skills and dang I worked, really, for several years as a bass player. I guess I continued with music in my own projects into my forties, with Love Maker and Starr. Love Maker, we were big in the city, and then Starr, I was the front man. Starr became pretty big. We got signed to Geffen records. And I was singing, we were playing it at the Continental, which doesn’t exist anymore, the Continental Club, you don’t know, you’re too young, that was the hot club, right off the St. Mark’s Place on Second or Third Avenue. There was some people, agents, there, and there was a TV show that they were developing, and they needed an evil rock band. It was a kids show, and they hired us to be this evil rock band because we had the big hair and the makeup.

MNG

Is there a band that sonically compared to you guys?

Z

I would say we were somewhere between early Mötley Crüe and Kiss. Kiss with the makeup and the costumes and the boots. We had custom costumes. We had the red suits, we had the black, we had silver, we had gold, you know, everything. We had somebody making us costumes. And we had a guy out in Queens that made the boots for us. We did the whole thing, you know. We did the TV show, we did a song for the show, and then we were going to go into the second season. Things were going great for us. We were touring, we were getting ready to go to Europe.

And then we got dropped by the record label. We were working on the record, and that stopped. Then the TV show did not continue the second season. And it was kind of like, oh shit. It was the right thing at the wrong time. It was like we were doing grunge and then rap. Look, I always say rap killed rock. That’s it, when the rap came out, the early rap.

MNG

Beastie Boys?

Z

Well, Beastie Boys, but like, like Coolio and, you know, “Funky Cold Medina”. I mean, I liked it too, but it killed rock. And that was kind of it. We still played a little... Jersey was big for rock. We would all play the big clubs in Jersey for hundreds of people, stuff like that. But it was over. We just knew that that was the end of it.

So I wound up getting involved in the wrong thing, and I started doing heroin. Boom, done. So I lost my house, sold my car... I sold my Jaguar to make money. Yeah, it’s a crazy story, and I had the wrong girlfriend, and guess what? That was it. I wound up in rehab. So it was crack. First, it was crack and it was always crack. I used to do it with the heroin. I never shot heroin, but I used to put the heroin and the crack in the pipe and smoke it together like a speed ball. What a high baby.

Anyway, I wound up in rehab. I came out. I was destitute. God bless my parents. When I came out of rehab my father picked me up, and they got me a room at the YMCA up by Columbus Circle. They bought me food. They wouldn’t give me money. They brought me food, cigarettes. They didn’t want me to have those, but they knew I needed them. And they bought me all arts. And I would stay, and I would work, and I did all this stuff.

I started doing the portraits. I’d find pictures in books. I’d go to the library. It was a library a couple of blocks away from my place in Brooklyn, the public library, and I would find, shouldn’t really say this, but I’d make two books, and I’d find pictures that I liked, and I’d rip them out take them back, and then sit and copy them. The first one I did that with is the David Bowie, which I still sell to this day.

MNG

When you started making prints in the early 2000s, what made you adopt this style so quickly? Was it your upbringing and your parents being into Japanese prints? Want to pull up a chair?

Z

Yeah. My ass hurts, yeah.

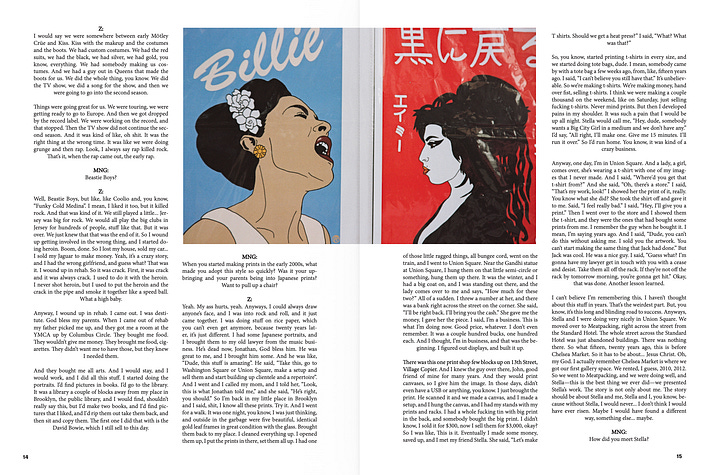

Anyways, I could always draw anyone’s face, and I was into rock and roll, and it just came together. I was doing stuff on rice paper, which you can’t even get anymore, because twenty years later, it’s just different. I had some Japanese portraits, and I brought them to my old lawyer from the music business. He’s dead now, Jonathan, God bless him. He was great to me, and I brought him some. And he was like, “Dude, this stuff is amazing”. He said, “Take this, go to Washington Square or Union Square, make a setup and sell them and start building up clientele and a repertoire”.

And I went and I called my mom, and I told her, “Look, this is what Jonathan told me,” and she said, “He’s right, you should.” So I’m back in my little place in Brooklyn and I said, shit, I know all these prints. Try it. And I went for a walk. It was one night, you know, I was just thinking, and outside in the garbage were five beautiful, identical gold leaf frames in great condition with the glass. Brought them back to my place. I cleaned everything up. I opened them up, I put the prints in there, set them all up. I had one of those little ragged things, all bungee cord, went on the train, and I went to Union Square.

Near the Gandhi statue at Union Square, I hung them on that little semi-circle or something, hung them up there. It was the winter, and I had a big coat on, and I was standing out there, and the lady comes over to me and says, “How much for these two?” All of a sudden. I threw a number at her, and there was a bank right across the street on the corner. She said, “I’ll be right back. I’ll bring you the cash.” She gave me the money, I gave her the piece. I said, I’m a business. This is what I’m doing now. Good price, whatever. I don’t even remember. It was a couple hundred bucks, one hundred each. And I thought, I’m in business, and that was the beginning. I figured out displays, and built it up.

There was this one print shop few blocks up on 13th Street, Village Copier. And I knew the guy over there, John, good friend of mine for many years. And they would print canvases, so I give him the image. In those days, didn’t even have a USB or anything, you know. I just brought the print. He scanned it and we made a canvas, and I made a setup, and I hung the canvas, and I had my stands with my prints and racks. I had a whole fucking tin with big print in the back, and somebody bought the big print. I didn’t know, I sold it for $300, now I sell them for $3,000, okay? So I was like, This is it. Eventually I made some money, saved up, and I met my friend Stella. She said, “Let’s make T shirts. Should we get a heat press?” I said, “What? What was that?”

So, you know, started printing t-shirts in every size, and we started doing tote bags, dude. I mean, somebody came by with a tote bag a few weeks ago, from, like, fifteen years ago. I said, “I can’t believe you still have that.” It’s unbelievable. So we’re making t-shirts. We’re making money, hand over fist, selling t-shirts. I think we were making a couple thousand on the weekend, like on Saturday, just selling fucking t-shirts. Never mind prints. But then I developed pains in my shoulder. It was such a pain that I would be up all night. Stella would call me, “Hey, dude, somebody wants a Big City Girl in a medium and we don’t have any.” I’d say, “All right, I’ll make one. Give me 15 minutes. I’ll run it over. So I’d run home. You know, it was kind of a crazy business.

Anyway, one day, I’m in Union Square. And a lady, a girl, comes over, she’s wearing a t-shirt with one of my images that I never made. And I said, “Where’d you get that t-shirt from?” And she said, “Oh, there’s a store.” I said, “That’s my work, look!” I showed her the print of it, really. You know what she did? She took the shirt off and gave it to me. Said, “I feel really bad.” I said, “Hey, I’ll give you a print.” Then I went over to the store and I showed them the t-shirt, and they were the ones that had bought some prints from me. I remember the guy when he bought it. I mean, I’m saying years ago. And I said, “Dude, you can’t do this without asking me. I sold you the artwork. You can’t start making the same thing that Jack had done.” But Jack was cool. He was a nice guy. I said, “Guess what? I’m gonna have my lawyer get in touch with you with a cease and desist. Take them all off the rack. If they’re not off the rack by tomorrow morning, you’re gonna get hit.” Okay, that was done. Another lesson learned.

I can’t believe I’m remembering this, I haven’t thought about this stuff in years. That’s the weirdest part. But, you know, it’s this long and blinding road to success. Anyways, Stella and I were doing very nicely in Union Square. We moved over to Meatpacking, right across the street from the Standard Hotel. The whole street across the Standard Hotel was just abandoned buildings. There was nothing there. So what fifteen, twenty years ago, this is before Chelsea Market. So it has to be about... Jesus Christ. Oh, my God. I actually remember Chelsea Market is where we got our first gallery space. We rented, I guess, 2010, 2012. So we went to Meatpacking, and we were doing well, and Stella—this is the best thing we ever did—we presented Stella’s work. The story is not only about me. The story should be about Stella and me, Stella and I, you know, because without Stella, I would never... I don’t think I would have ever risen. Maybe I would have found a different way, something else... maybe.

MNG

How did you meet Stella?

Z

In Union Square. She was selling jewelry. She was a collector of all kinds of weird jewelry, and I liked her look. I always said she reminded me of a perfect cross between Johnny Thunders and Patti Smith. That’s what she looked like. And I saw her profile, and I walked over to her while I was selling, and we just became friends. And actually, I fell in love. We, you know, we became lovers and everything for a while.

But anyway, she made these things. I went to the hardware store, I got them varnished, and I fixed them up, and I took them out to Meatpacking one day with my stuff on the wall, and I had these leaned up against the wall. The guy in the Mercedes Benz drives up, pulls over. He said, “How much for that?” I said, “Well, that’s not my work, this is my work” (gesturing). He says, “Well, I know your work. How much for those?” (Stella’s.) I was like, okay, I threw a number at him, he pops the trunk, towel in the back, paid me $500 cash for it. I called Stella. I said, “Now you’re a working artist. Come and get your money, honey.” That started everything.

So then we started bouncing off of each other, and then we spent some time where I just gave my work a powder, because hers became very lucrative, because now you’re not selling prints for like, one hundred bucks. Now you’re selling paintings for, like, a lot more, you know, because she’s an abstract. She’s not a printer. She’s a painter. Yeah, she’s a real painter. I sold a painting for her, this past Saturday or Saturday. Over there—$3,000 in the street. That’s hard to get these days, you know? Yeah. So she sells good and over time we’ve developed her client base. And I’ll take certain days and sell only her work, and then I’ll have my days where I come and do my shtick. And we pretty much have been doing the same thing for the last fifteen years, you know, still have a partnership. Yeah, still Stray Kat Gallery. We did Stray Kat Gallery. That’s how it came.

MNG

I remember that one in the West Village.

Z

Before that we were in Chelsea Market. And we were killing it. Our paintings and my prints. We were making money. We were making money. Then that stupid Artisan Fleas thing came, and they wanted the space, and so they got it. But the people from Chelsea Market were like, “We have a spot on 14th Street right at the High Line. Tell you what. Give it to you. $6,000 a month.” We took that. So we did Chelsea Market after doing Meatpacking. No more street. Now we have gallery space. We have our first gallery space. We’re doing events. We’re doing the whole thing, you know, wine and whatever.

So when Artisan Fleas wanted that space and our lease was up, they were like, “You know what? We have a spot for you. Give you a great deal.” Now we were at the staircase of the High Line. Across the street there was another spot that was rented. It was interesting. We did okay at the first spot, but then the people moved out across the street—it wasn’t the Chelsea Market. I forget the company that owned it. This was an 8,000 square foot space with thirty-foot ceilings. It was insane. Wasn’t properly lit, but we found out who owned it and who controlled it, and they gave us a decent deal, and we took that. We moved right across the street. Wasn’t properly lit.

I remember we had fifty can lights, and I’ve gone ladder hanging, slipping into stuff with wires tacking into the wall with electricity. Made a fucking great gallery. We started cleaning up again right there. And it was just like, why did the chicken cross the road to make more money? We were here and we went there, and it was night and day. It was unbelievable. But the space had a certain... certain... it was just... It wasn’t really a finished space. It was really cool. Cool with the artwork, with the big posters and Stella’s big paintings. And then people from Europe and tourism. It was just the right thing.

MNG

What was the creative bond? So you guys met, you hit it off from a personal standpoint. But she saw your art and saw an opportunity to expand the way you do it?

Z

Yeah, she had the brain. And it was like, Look, if Jack could make t-shirts, why don’t we make t-shirts? And she’s very smart, very forward thinking, whereas I just run with the wind, you know? I mean, whatever. Oh, it’s working. I’m just gonna keep doing it. She’s like, well, this is working. She’s more—

MNG

She has the vision.

Z

Yeah, she’s the business. I will say that she has a great vision, very smart lady. I’ll never take that away from her. So that big gallery in the West Village, yeah, then we got the space on Jane Street. It’s a beautiful corner. Remember that corner?

MNG

Of course. That was a great spot. I went to your Gallery during COVID. Bought the Miles Davis. Pink and Blue.

Z

We had that for three years. Yeah, that fucking place. Whoa. We got it right before COVID, and then COVID hit, and then everything shut down. And you know what I did: I kept it open. I would go in the late afternoon. I’d leave the lights on all the time, and I would go in the late afternoon, stay open all night, and people would come out for their walk after the day of being in their apartment. They gotta walk their dog and take a walk after dinner, smoke a cigarette. And people were coming in and buying shit. I was making money right during COVID. I would say we won by default, because we were the only game in town.

I was open, and all of a sudden somebody complained: “Why is that guy open?” No stores were supposed to be open. Three cops came. They’re like, “Hey, what’s going on?” And I said, “Hey, what’s up?” “You have people in here?” I said, “Yeah, well, by appointment.” I had a sign on the door: By Appointment Only. I said, “Yes, you know, I have somebody coming over, so that’s why.” But it was a nice day. I didn’t need the air conditioning. It wasn’t cold. I had the door open, and they were looking around. They said, “Wow, this is some cool stuff. Listen, as long as you don’t have more than six people in here at one time, including yourself, you can stay.” So that was the end. I got to pass by the cops. Hell yeah. So I was in like Flynn.

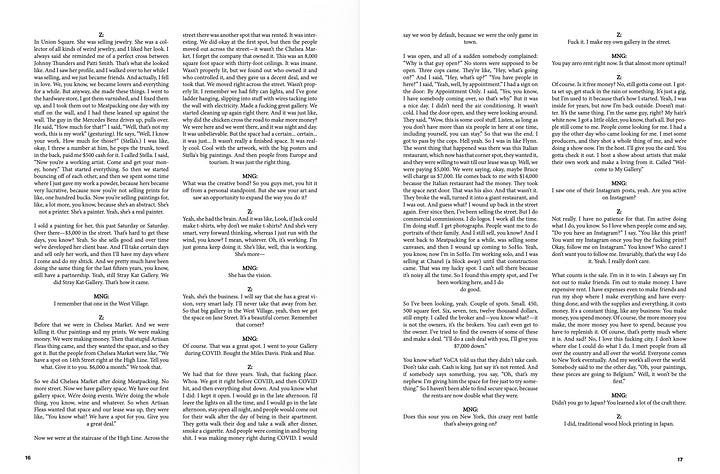

The worst thing that happened was there was this Italian restaurant, which now has that corner spot, they wanted it, and they were willing to wait till our lease was up. Well, we were paying $5,000. We were saying, okay, maybe Bruce will charge us $7,000. He comes back to me with $14,000 because the Italian restaurant had the money. They took the space next door. That was his also. And that wasn’t it. They broke the wall, turned it into a giant restaurant, and I was out. And guess what? I wound up back in the street again. Ever since then, I’ve been selling the street. But I do commercial commissions. I do logos. I work all the time. I’m doing stuff. I get photographs. People want me to do portraits of their family. And I still sell, you know?

And I went back to Meatpacking for a while, was selling some canvases, and then I wound up coming to SoHo. Yeah, you know, now I’m in SoHo. I’m working solo, and I was selling at Chanel (a block away) until that construction came. That was my lucky spot. I can’t sell there because it’s noisy all the time. So I found this empty spot, and I’ve been working here, and I do do good.

So I’ve been looking, yeah. Couple of spots. Small. 450, 500 square feet. Six, seven, ten, twelve thousand dollars, still empty. I called the broker and you know what?—it is not the owners, it’s the brokers. You can’t even get to the owner. I’ve tried to find the owners of some of these and make a deal. “I’ll do a cash deal with you, I’ll give you $7,000 down.” You know what? VoCA told us that they didn’t take cash. Don’t take cash. Cash is king. Just say it’s not rented. And if somebody says something, you say, “Oh, that’s my nephew. I’m giving him the space for free just to try something.” So I haven’t been able to find secure space, because the rents are now double what they were.

MNG

Does this sour you on New York, this crazy rent battle that’s always going on?

Z

Fuck it. I make my own gallery in the street.

MNG

You pay zero rent right now. Is that almost more optimal?

Z

Of course. Is it free money? No, still gotta come out. I gotta set up, get stuck in the rain or something. It’s just a gig, but I’m used to it because that’s how I started. Yeah, I was inside for years, but now I’m back outside. Doesn’t matter. It’s the same thing. I’m the same guy, right? My hair’s white now. I got a little older, you know, that’s all. But people still come to me. People come looking for me. I had a guy the other day who came looking for me. I met some producers, and they shot a whole thing of me, and we’re doing a show now. I’m the host. I’ll give you the card. You gotta check it out. I host a show about artists that make their own work and make a living from it. Called “Welcome to My Gallery.”

MNG

I saw one of their Instagram posts, yeah. Are you active on Instagram?

Z

Not really. I have no patience for that. I’m active doing what I do, you know. So I love when people come and say, “Do you have an Instagram?” I say, “You like this print? You want my Instagram once you buy the fucking print? Okay, follow me on Instagram.” You know? Who cares? I don’t want you to follow me. Invariably, that’s the way I do it. Yeah. I really don’t care.

What counts is the sale. I’m in it to win. I always say I’m not out to make friends. I’m out to make money. I have expensive rent. I have expenses even to make friends and run my shop where I make everything and have everything done, and with the supplies and everything, it costs money. It’s a constant thing, like any business: You make money, you spend money. Of course, the more money you make, the more money you have to spend, because you have to replenish it. Of course, that’s pretty much where it is. And sad? No, I love this fucking city. I don’t know where else I could do what I do. I meet people from all over the country and all over the world. Everyone comes to New York eventually. And my work’s all over the world. Somebody said to me the other day, “Oh, your paintings, these pieces are going to Belgium.” Well, it won’t be the first.”

MNG

Didn’t you go to Japan? You learned a lot of the craft there.

Z

I did, traditional wood block printing in Japan.

MNG

Since then you’ve been clean?

Z

I did slip once or twice, until I met Stella, and I let it go.

MNG

So Stella was huge for you...

Z

Yeah, yeah. Because, like, even when I got out, I was like... I think Stella saved my life.

MNG

Did you ever consider settling with her? Where is the business you have together now?

Z

Stella. Oh, yeah. We were settled in a way, but we were so involved in what we were doing. And she’s selling, and we’re making money, and we’re gonna sell you (Stella’s work) today. We sell me too. It was an exciting thing. So you could come from the street, save $20,000 and rent a space, and all of a sudden you have a gallery. You came from nowhere, you’re selling in a park, and the next thing you know, you opened up your own space, just from hard work, being smart, just making it happen. And I credit Stella a lot for that because, like I said, me, I’m great at making money. I’m even better at spending it. Trust me. That’s really the story of my life.

MNG

Speaking of spending money. How about New York? Do you think it’s still a good place for young artists? I mean, you’re kind of a part of the old guard.

Z

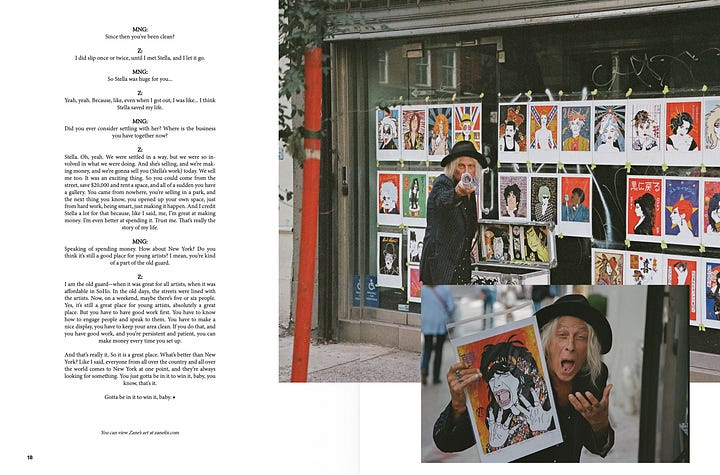

I am the old guard—when it was great for all artists, when it was affordable in SoHo. In the old days, the streets were lined with the artists. Now, on a weekend, maybe there’s five or six people. Yes, it’s still a great place for young artists, absolutely a great place. But you have to have good work first. You have to know how to engage people and speak to them. You have to make a nice display, you have to keep your area clean. If you do that, and you have good work, and you’re persistent and patient, you can make money every time you set up.

And that’s really it. So it is a great place. What’s better than New York? Like I said, everyone from all over the country and all over the world comes to New York at one point, and they’re always looking for something. You just gotta be in it to win it, baby, you know, that’s it.

Gotta be in it to win it, baby.